Small dogs need big personalities for you to “listen” to them.

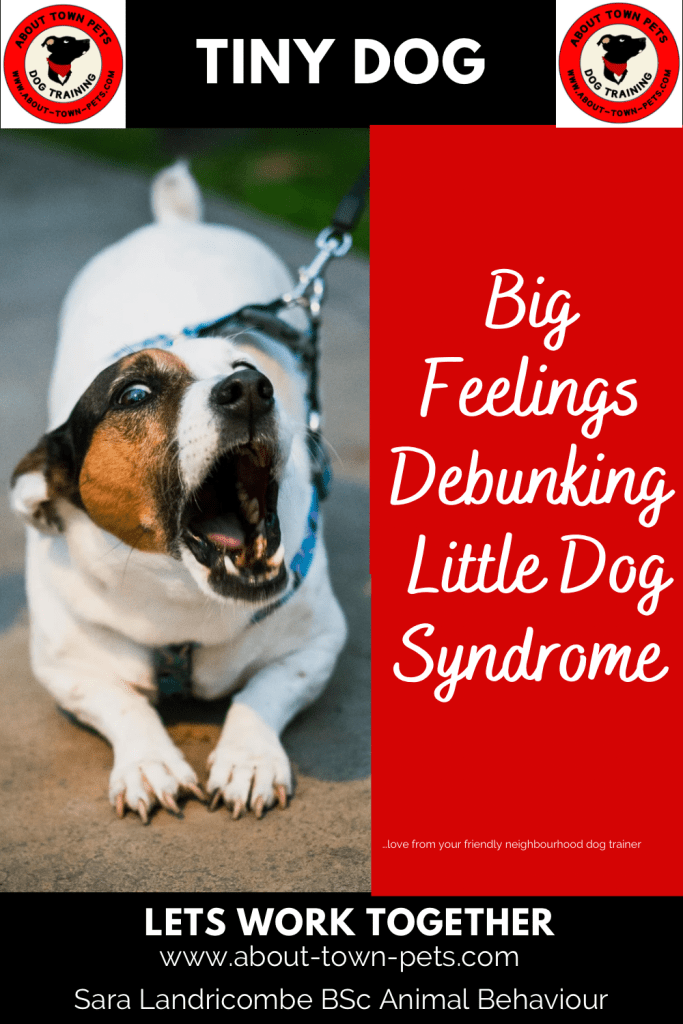

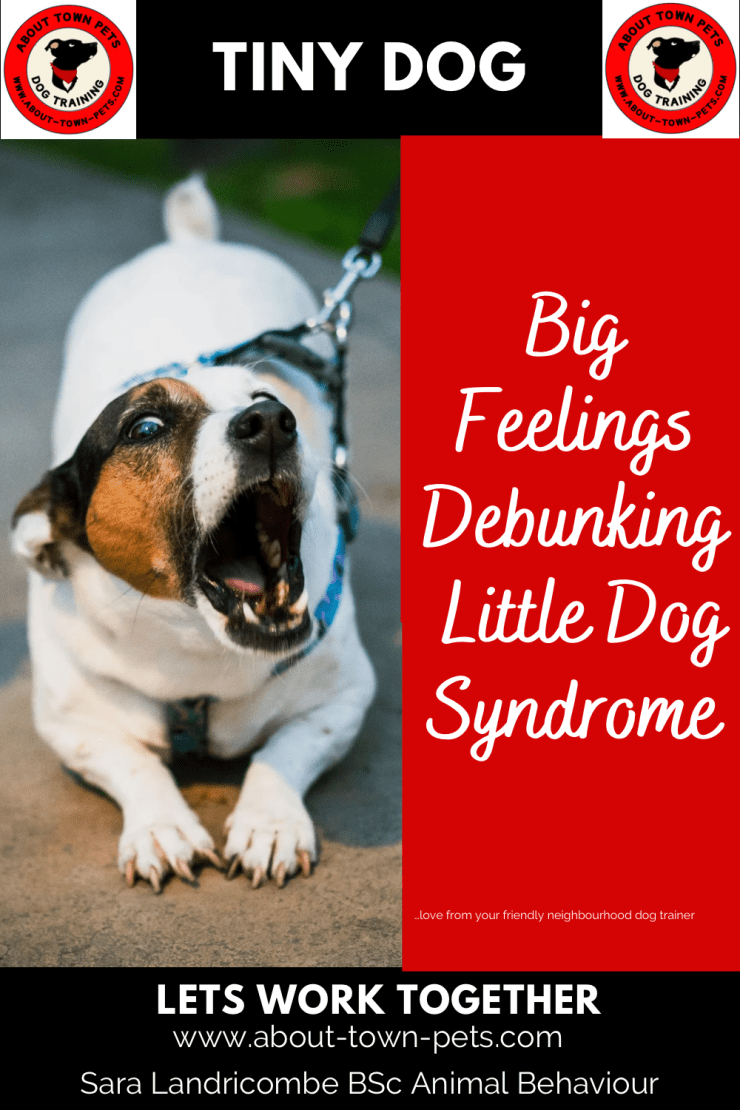

If you’ve ever heard the phrase “little dog syndrome”, you might picture a tiny dog with big attitude—yapping, bossing other dogs around, maybe even snappy or reactive. It’s a phrase many people toss around with a wink. But as with many catchy sayings, the reality is far more nuanced than it seems.

What the phrase implies

The term suggests that small-breed dogs are inherently more problematic: more yappy, more aggressive, more spoiled. It frames size as the root cause of behaviour problems. But the truth: size alone doesn’t determine behaviour. What does matter is why behaviour issues arise — and how we support small dogs (and their owners) differently.

What the science reveals

- Research shows that smaller dogs do have higher odds of owner-reported fearfulness and aggression than larger dogs — but size is just one of many factors. For example, one large-scale study found that smaller body size correlated with higher risk of fear and aggression, but the authors emphasised that this is a broad, population-level trend, not a destiny for any individual dog.

- Another key piece: early life and maternal care matter a lot. Puppies whose dams were less stressed, who gave more consistent licking/nursing and contact, develop into calmer, more resilient adults.

- Behaviour issues in small dogs are frequently driven by pain or medical issues (for example dental disease, joint problems, airway or spine issues) rather than “just being a small dog with attitude.” When pain is relieved, behaviour often improves.

- Nutrition and training style matter too: diet can support behaviour improvement (though it isn’t a silver bullet) and training methods that rely on rewards, respect and clear communication outperform punitive methods — especially for smaller dogs.

So what’s really at play?

Here are the bigger drivers behind what gets labelled “small dog syndrome”:

- Higher vigilance: Many small breeds were bred to alert or watch (rather than herd or guard). That means a lower threshold to respond to stimuli (doorbell, stranger, passer-by).

- Owner handling biases: Small dogs are easier to pick up, more likely to be carried, less likely to be handled like larger dogs (walked as much, trained as much). This can reduce their confidence and increase fear.

- Overlooking health issues: Because they’re small, pain or discomfort in the joints, spine, teeth or airway may be overlooked — and an irritable, anxious dog often looks like a behaviour problem.

- Inadequate training/enrichment: Smaller dogs still need outlets for their breed-instincts, socialisation, movement and mental challenges — these get missed if we think “small = easy.”

- Environment and management: Running into strangers, dogs or stimuli at high speed without a plan creates stress; small dogs are more vulnerable to feeling “trapped” (less body mass, fewer escape options) so reading early signals matters.

What you can do to advocate for your small dog

1. Read the body language early

Look for the subtle-before-the-problem: lip licks, head turn, freezing, shifting weight, crouching or making the body smaller. These aren’t “cute” — they’re stress signals. Intervene early: give space, create a barrier (your body, a bench), redirect to a positive behaviour (scatter a few treats, hand-target, escort to safe zone).

2. Check health/pain before punishing behaviour

Especially in small breeds, do a “vet audit” when you see a new or changed behaviour: dental examination (crowded jaws are common); joint check (patella, spine/neck, hips); airway/trachea or breathing issues; signs of neuropathic pain (especially in certain breeds). Pain-driven behaviour is teachable — but only after treating the cause.

3. Tailor training to small-dog size & needs

- Use a well-fitted Y-front or front-clip harness instead of a tight collar (especially for toy or brachycephalic breeds)

- Teach “station” (mat on the floor or low bench) so your small dog has a safe base

- Practice “hand-target,” “middle” (dog between your legs), “scatter-sniff” breaks during walks

- Use short sessions frequently (2–3 mins several times a day) to suit small body/attention spans

- Build “consent handling” (dog comes to you for grooming/touch rather than you always picking it up) to build resilience and trust

4. Provide enrichment & mental outlets

Small breed owners often think “less space = less need.” But with little dogs especially, enrichment helps reduce reactivity and fear: puzzle feeders, snuffle mats, short high-value walks, nosework, training games, “Look at that” with new people/dogs at distance.

5. Change the narrative: dismissing “small dog = easy”

Educate your network: small dogs can do a lot — we just need to support them right. They deserve the same structured socialisation, and predictable training, and patience. The phrase “small dog syndrome” stops being an excuse and becomes a stepping-stone to doing better.

6. Create safe walks & encounters

Because small dogs are physically closer to obstacles, less body-mass to buffer stress, teach your clients / owners to anticipate:

- Use visual scanning: what’s ahead? Could another dog/child move towards us quickly?

- If yes: U-turn early or cross the road, give space.

- If in doubt keep moving – lead reactivity is often an attempt to create space if we take on the role of manager we can always help the dog out and keep moving- knowing your dogs initial safe distance is important.

- Practice a “go-to” cue like “find it” then drop a handful of treats behind a parked car or something else in the environment to help to block the oncoming trigger just until the moment has passed.

- Use a “safe space” or magic mat at dog-friendly cafés or venues so your dog can climb up, feel elevated and choose to stay. Being sure that everyone understands to “ignore” your dog where needed.

Final word

Your little dog isn’t “just small.” It’s a fully capable, complex individual with specific needs. Yes—size adds a few extra risk parameters (fear threshold, vulnerability to pain, owner biases) but it never dictates the future. By understanding the science (maternal care, early life, genetics, health, training), reading the signals early, and advocating smartly, you turn “small dog syndrome” from a myth into an opportunity: a chance to say “small dogs count too—and actually, they hold the key to some of the best, most fun, most rewarding dog-human partnerships.”

Let’s shift the conversation: small dogs deserve big support.

And if you found this blog helpful you might also like my previous blog post on 👇

… love from your friendly neighbourhood dog trainer – S

If you want to work with me 1-2-1 please check out my Training & Behaviour Questionnaire Link To Get Started HERE 🐶

—

Please consider signing up to my Weekly Newsletter to find out about all upcoming online session and in person sessions available over the next few weeks.

[…] And if you found this blog post helpful please check out my previous blog post here – Debunking the “Little Dog Syndrome” Myth […]

LikeLike